Although we have been to Rome many times, it always seemed as though there was never enough time to see and do everything we wanted. So in mid-January, we rented an apartment for an entire week.

Spoiler alert – there still wasn’t enough time. Rome is known as the Eternal City – perhaps because it would take an eternity to explore it. But we enjoyed our still-too-brief stay nevertheless.

Our apartment was in the San Giovanni district, a residential area around and just outside the ancient city walls, and close to the Vatican church of San Giovanni Laterano (St. John Lateran) for which it is named.

San Giovanni is a mostly residential district, and is therefore full of businesses serving places where real people live – supermarkets, produce vendors, moderately-priced cafes and restaurants, shops selling food to go like roast chicken – even laundromats. And the district is well connected by Metro and bus lines to the more heavily touristed parts of the city.

It’s a good thing the area is well connected to Rome’s public transportation services, since it’s a very difficult area to find parking. We used a garage, but many Romans have a more creative approach to finding a place to leave their cars.

In January, there are far fewer tourists than in the summer, although the area around the Colosseum was still pretty crowded. For the most part, though you could move around the city without feeling oppressed by throngs of people. And we were blessed with good weather, with daytime highs near 60 degrees, sunny skies, and no rain. It’s a very nice time to visit Rome. (Maybe I should have kept quiet about that….)

Here are some of the highlights of our trip.

Vatican Churches

In addition to Saint Peter, the Vatican operates four churches in the city of Rome. Two of them, San Giovanni in Laterano and Santa Maria Maggiore, were within walking distance of our apartment.

There has been a church on the site of San Giovanni in Laterano since the 4th Century, although the current church dates only to the 16th Century, after a major fire destroyed the older structures. Like most Vatican churches, it is massive in scale, including greater-than-lifesized statues in niches lining the nave.

We were more drawn to the peaceful 13th C cloister, with its funerary monument by Arnolfo di Cambio.

The basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore dates to the 5th C and is also massive in scale. It has been subject to several major renovations during the succeeding centuries. As a result, the interior is kind of a hodge podge of artistic styles, including both a 13th Century presepe sculpted by Arnolfo di Cambio, and a 6th Century icon of the Madonna encased in a Baroque frame.

One significant 16th Century renovation was done during the administration of Pope Sixtus V, who was born in Grottammare (near where we are currently living) and is buried here. Note the inscription “In Piceno Natus”.

Mosaics

I always enjoy looking at mosaics in Roman churches. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the city of Rome was something of a backwater – the population fell from over a million in the imperial period to an estimated 50,000 by the 15th Century. For many centuries, people mostly struggled to survive. Ancient sites, and even early Christian churches, fell into disrepair, and many were abandoned. But even in this dark era, there was some artistic and cultural activity, mostly centered around the Roman Catholic church.

The basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, noted above, has some of the oldest mosaics in Rome, dating from the 5th Century.

More mosaics were added in the 12th and 13th Centuries.

The basilica of Santa Prassede, near the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore , was built in the 8th Century to hold the relics of two women martyrs from the late Roman era. The 9th Century mosaics, although clearly influenced by the tradition of the then-dominant Byzantine models, have a design all their own.

The church of Santa Maria in Trastevere was founded in the 4th Century, with the current structure dating from the 12th Century. The Cosmati family’s mosaic floor, often using mosaics from Roman ruins, proved so popular that the floors are now called “stile cosmatesco.” The columns also were recycled from older Roman buildings, including the Baths of Caracalla, which helps explain why they are not evenly matched.

The interior features mosaics by Pietro Cavallini, a painter and mosaic designer working in the late 13th C. The scenes from the life of the Virgin are still done in the flat-perspective Byzantine style. But the facial features have a liveliness that prefigures the Renaissance. And when Jesus is shown with his arm around Mary’s shoulders, it’s less of the formal Byzantine presentation than a nice young man showing off his mother to the world.

Forma Urbis

It’s not every day that you get a new monument from ancient Rome. But this year, there is one – the Forma Urbis. In the early 3rd Century, the emperor Septimius Severus ordered a map be made of the entire city, based on the most recent census. Every building in Rome was represented – dwellings, warehouses, porticoes, temples and shops – each identified by markings distinguishing the type of building. Late Imperial Rome is believed to have had a population of about 1,000,000. That’s a lot of housing, even though people lived in much smaller quarters than we do today. The map is about four stories high, and is believed to have been mounted upright at the entry to the Forum – a sort of “Welcome to Rome” sign advertising the city’s wealth and power.

Pieces of the map started being dug up in the 16th Century, and fragments were lost or dispersed until they were finally put into museum storage for safekeeping n the 18th Century. Today, only about 10% of the original map remains, many in pieces so small their position on the overall map cannot be determined with certainty.

In order to make sense of the fragments that remain, the curators have arranged the surviving pieces on the floor, superimposed on an 18th Century map by Giovanni Batista Nolli, like a giant jigsaw puzzle. It’s an incredible artifact.

Capitoline Museum and Phidias Exhibit

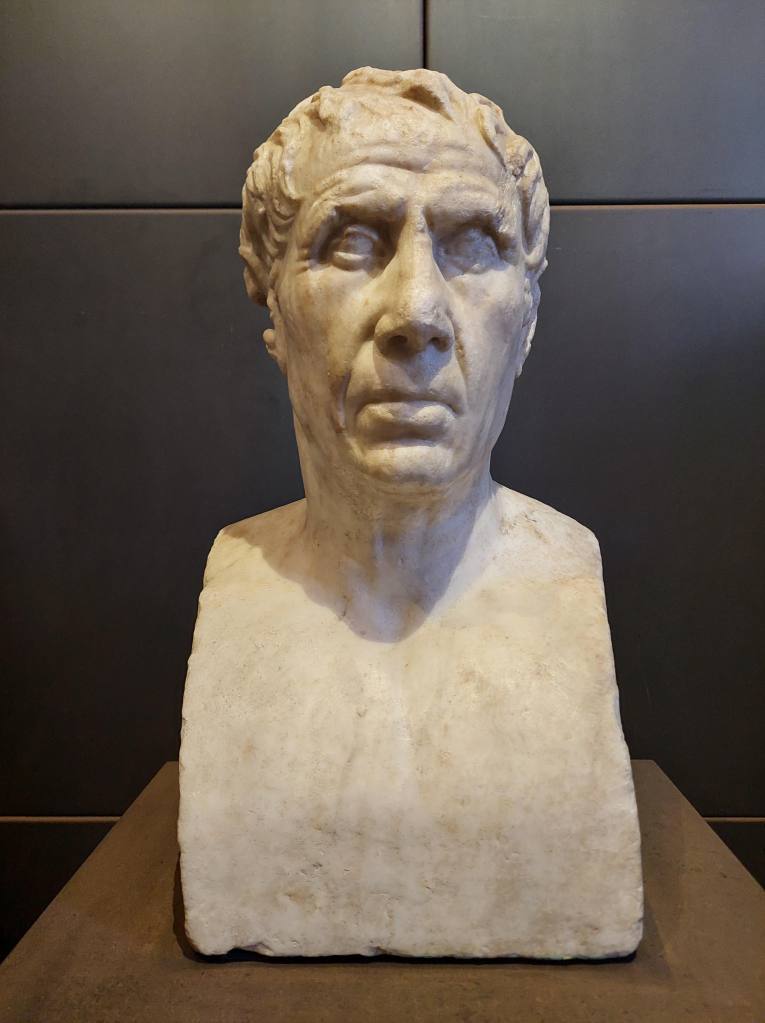

The Capitoline Museum, at one end of the Roman Forum, has the most important collection of ancient Greek and Roman statuary in Rome. Opened to the public in 1734, it is one of the oldest public museums in the world, and it has an incredible collection of ancient sculpture. Somewhat surprisingly given the high quality of the art, it is often not very crowded.

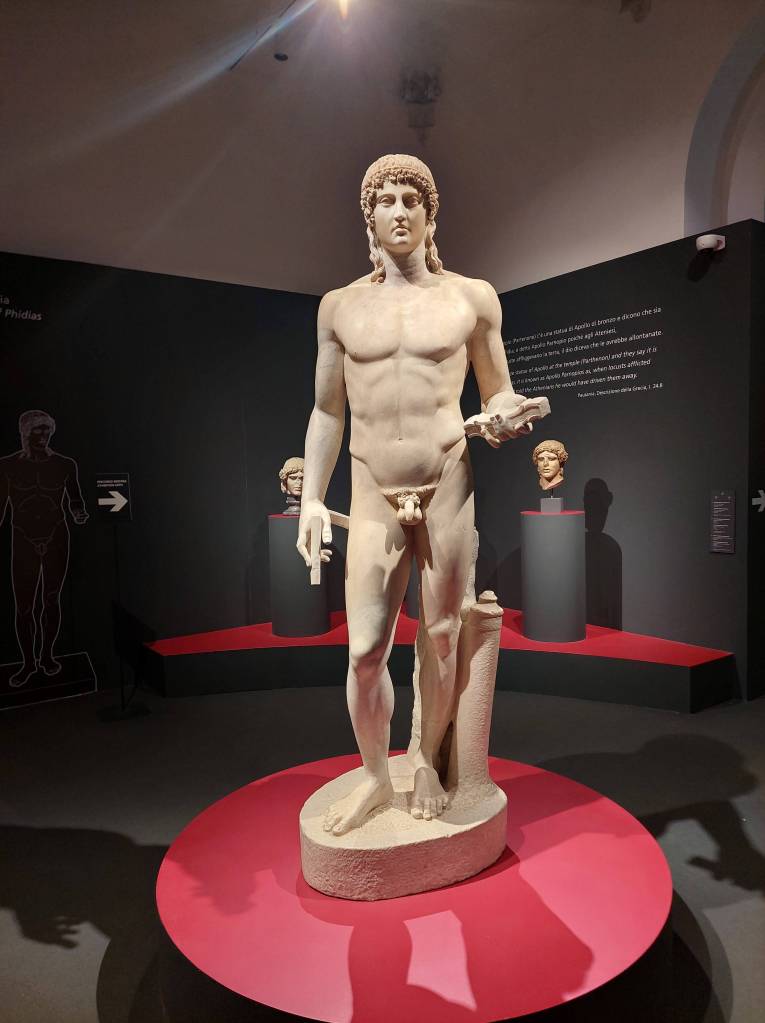

During our visit, part of the museum space was devoted to Phidias, one of the most important sculptors of ancient Greece. Phidias’ work was extremely popular in ancient Rome, and much of what we know about the many works of Phidias which have been lost comes from Roman copies.

Phidias is believed to have been the supervising architect of the Parthenon, and to have designed the friezes around its exterior. One room in the exhibit was devoted to the removal of pieces of the external sculpture and their subsequent installation in the British Museum – the so-called “Elgin Marbles.” The exhibit’s curators took a dim view of this operation – not surprising, since the Italian government has itself been involved in a number of struggles with foreign museums trying to get back ancient artifacts. Interestingly, the exhibit included some letters from 18th Century Englishmen then living in Athens, expressing disquiet about the operation, and suggesting it was controversial even in its own day.

The Capitoline also exhibits paintings from later periods, including works by Caravaggio, Goya and Velazquez.

And the terrace behind the museum offers one of the best views of the ancient Roman Forum.

Galleria Borghese

We have been to this museum many times and still can’t get enough of it. The collection, while small (you can see everything in less than 2 hours) is stupendous. If you only have a short time in Rome, this is the museum to see.

The museum includes several outstanding works of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, as well as several paintings by Caravaggio.

Venetian painters are well represented.

I was charmed by this portrait by Raphael, of a woman cradling a baby unicorn – a fantasy element in an otherwise realistic painting.

The model for this painting of John the Baptist by Agnolo Bronzino is believed to have been Giovanni de Medici, younger son of Duke Cosimo I, who was to die tragically young of malaria in 1562.

I also liked this portrait by Parmigianino.

And this portrait of a very assertive Venus, by Lambert Sustris, a Dutch painter who worked in Italy, seems to prefigure Manet’s Olympia.

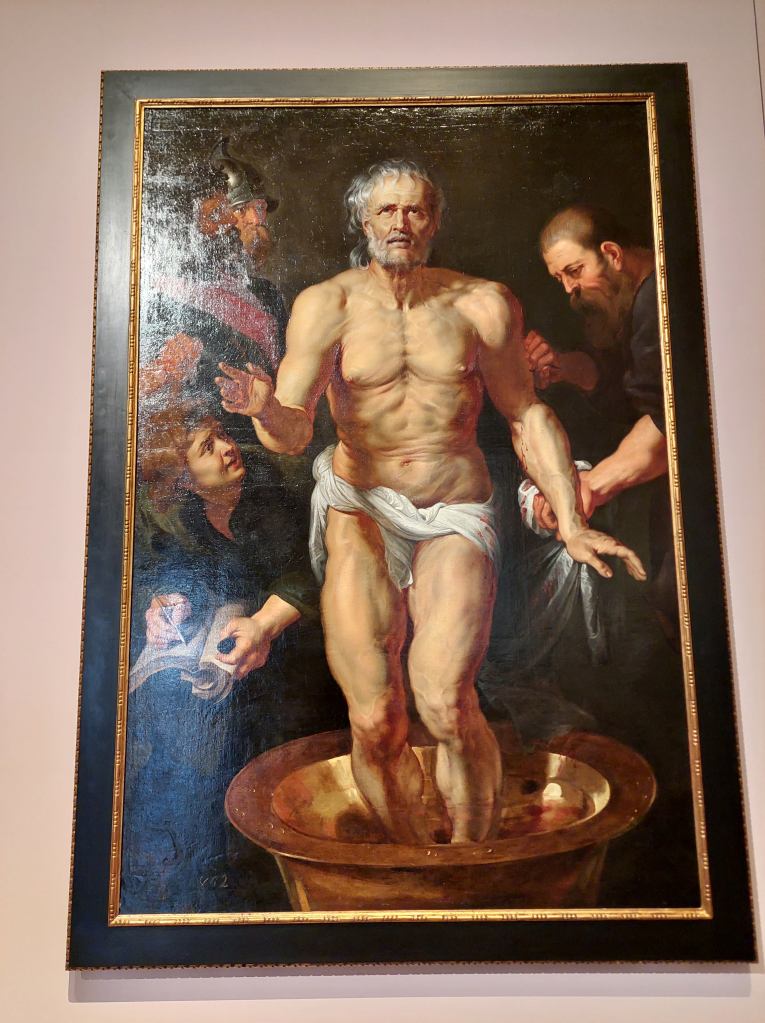

As if its regular offerings weren’t enough, the Borghese often has small special exhibits, this time featuring the work of Peter Paul Rubens. Rubens it known for his monumental paintings, sometimes covering entire walls. So it was nice to see some of his smaller works.

I particularly liked his animal sketches.

This museum, even before Covid, had imposed restrictions on the number of visitors. So advance reservations (with a timed entry) is essential. There were a few spots reserved for walk-in visitors. But there are only 13 unreserved slots available per hour, and even on a midweek in January, there was a line. On this visit, I noticed that the museum had abandoned the prior practice of emptying the museum every two hours in favor of a simpler system, selling so many entries per hour. But they don’t throw you out anymore if you want to stay a little longer.

Borromini Churches

We saw two churches by Francesco Borromini, an outstanding architect of 17th Century Rome whose reputation is usually overshadowed by his more famous contemporary Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

The two Borromini churches we saw were on constrained building sites, and his innovative use of geometrical forms in his building plans, the alternation of convex and concave surfaces, tricks the eye into believing the interiors are much larger than they actually are.

The church of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, built between 1642 and 1660, is widely regarded as one of his masterpieces. It is famously hard to get into – it’s officially open only three hours a week (Sunday morning 9-12) and sometimes not even that, because they often hold services on Sunday morning during which visitors are expected to leave. So we were there on the stroke of 9, and followed the caretaker in.

The church, which looks like a small square building from the outside, has a circular interior, giving the sense that the entire church is the interior of a large dome.

Note that the facade of the church is concave, which gives the effect that the church is a continuation of the courtyard arches (which were, in fact, designed by another architect).

Borromini was a master of using alternating convex and concave surfaces, which sometimes means that interior features look different depending on where you are observing them from.

Note the arch over the altar, which looks normal when viewed from one of the corners, looks a bit squished when viewed from close range. Note also the tesselated pavement floor, which creates an illusion of movement.

Similarly, interior of the dome looks different depending on where you are observing it from. One way he tricks the eye is that the windows associated with the round sections of the dome are larger than the ones associated with the edges.

The church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, also called San Carlino, was built by Borromini between 1638-1641. By walking up and down the side aisles, you could see how Borromini used a slight curvature in the columns and the arches to make them appear bigger than they actually were. Even the candlesticks are curved, to heighten the optical effect.

In the accompanying cloister, he tricked the eye by differentially spacing the columns.

I feel like I could spend months inside one of Borromini’s churches and still not understand the math, and how he achieves the optical illusions the way he does.

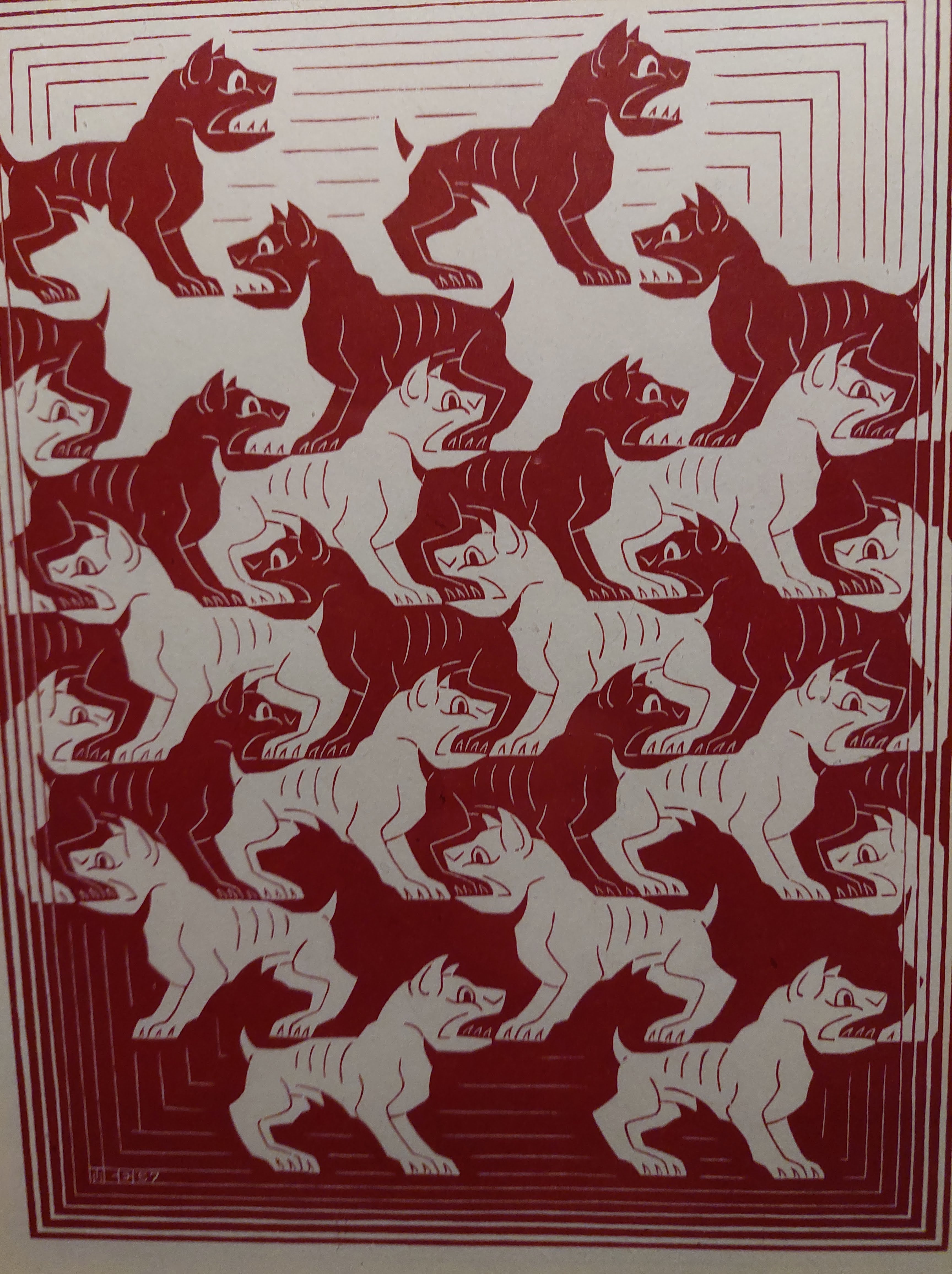

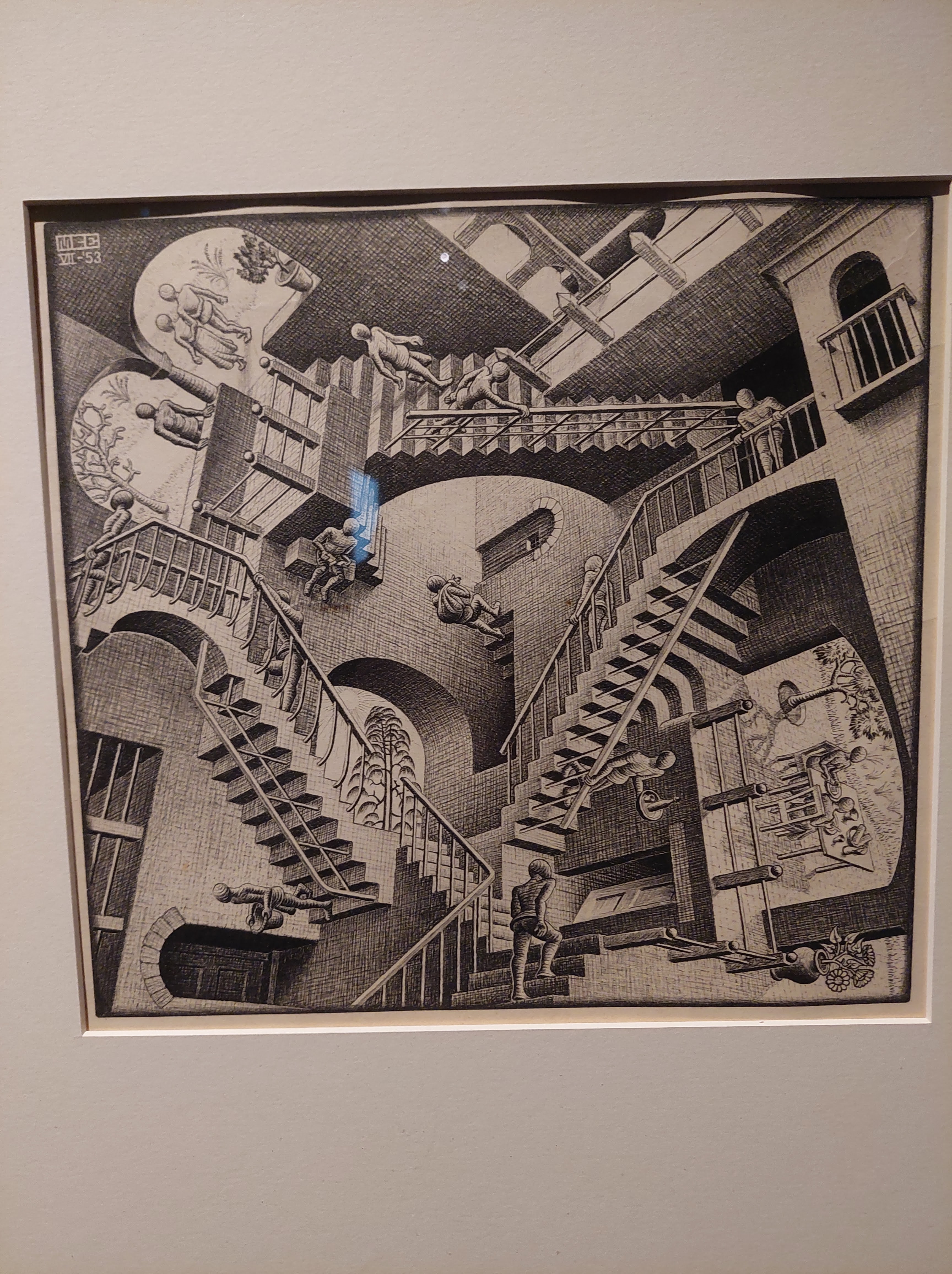

Escher Exhibit

We didn’t realize it at the time, but the exhibit of works by M.C. Escher, a Dutch graphic artist, was a perfect complement to our visits to the Borromini churches. Escher lived in Rome for 12 yeas, in the 1920s and early 1930s, and was obviously influenced by the centuries of Italian art he could see in the city.

It’s hard not to see the influence of Borromini, for example, in this work by Escher.

Escher also did a lot of work with tesselations, although unlike the Baroque artists, he used animal forms as well as geometric ones.

Escher is most famous for his impossible geometries, which were well represented in the exhibit.

He also did representations of the Mobius Strip – by tying two ends of a strip of paper together with a half twist, you create an object with a continuous surface. This topological object, a way of representing a fourth dimension in three-dimensional space, was described by August Mobius in the 19th Century. But in fact representations of it can be seen in later Roman mosaics going back to the 3rd Century – something I suspect Escher was aware of.

Escher’s work with geometrical forms is probably one reason he was a favorite of mathematicians.

But Escher was an artist, too, using geometry to create some pretty evocative work.

Other Museums

There are so many spectacular things to see in Rome that tourists often overlook many smaller but fascinating museums, especially on a short visit.

One of these unjustly overlooked museums is the Etruscan Museum, one of the most important collections of Etruscan artifacts in the country.

Most of what we know about the Etruscans comes from the things they left behind in their tombs and funerary monuments – the painted tombs of illustrious citizens, men as well as women, were noticeably opulent.

Perhaps the most fascinating artifact is the so-called Sarcophagus of the Spouses, dating from the 6th Century BC, commissioned by a husband and wife who apparently wanted to stay together for all eternity.

Etruscan society was hardly isolated – their artifacts indicate familiarity with a number of different cultures that traded in and around the Meditteranean.

This portion of a temple frieze from Pyrgi, an ancient Etruscan city down the coast from modern Civitavecchia. depicts a scene from Greek myth of Seven Against Thebes, about a war between the sons of Oedipus. in his frieze, one of the warriors, Tydeus, is depicted eating the brains of his opponent, Melanippus.

This vase, dating from the 6th Century BC, is a very early depiction of women with strikingly different racial features.

We paid a brief visit to the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna (the Gallery of Modern Art), popularly known as GNAM. In Italy, “modern art” means anything created from the 19th Century forward.

The museum has a large space for a relatively small collection. But their works are often imaginatively presented, as in the side by side display of portrait busts done by Italian sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini, done in the 1830s, next to a work by French sculptor Auguste Rodin, done about 50 years later. A big change in artistic styles in just a few decades.

I love this painting by Giuseppe de Nittis, an Italian Impressionist who worked in Paris. The racetracks around Paris are frequent subjects for the Impressionist painters. But only De Nittis shows us the brazier around which most of the well-dressed women huddled. De Nittis, who grew up in southern Italy, must have been cold.

One of the great pleasures in visiting these less well-known museums is that you can suddenly find yourself alone with spectacular paintings like these.

When we last visited the Doria-Pamphili Museum, about 10 years ago, we were disappointed to find that the museum’s outstanding art collection was displayed in the original 18th Century manner – arranged on three levels, forcing you to crane your neck to see the ones mounted higher up. They have rearranged their exhibit space, and now some of their most important paintings, like these three Caravaggios, have their own room.

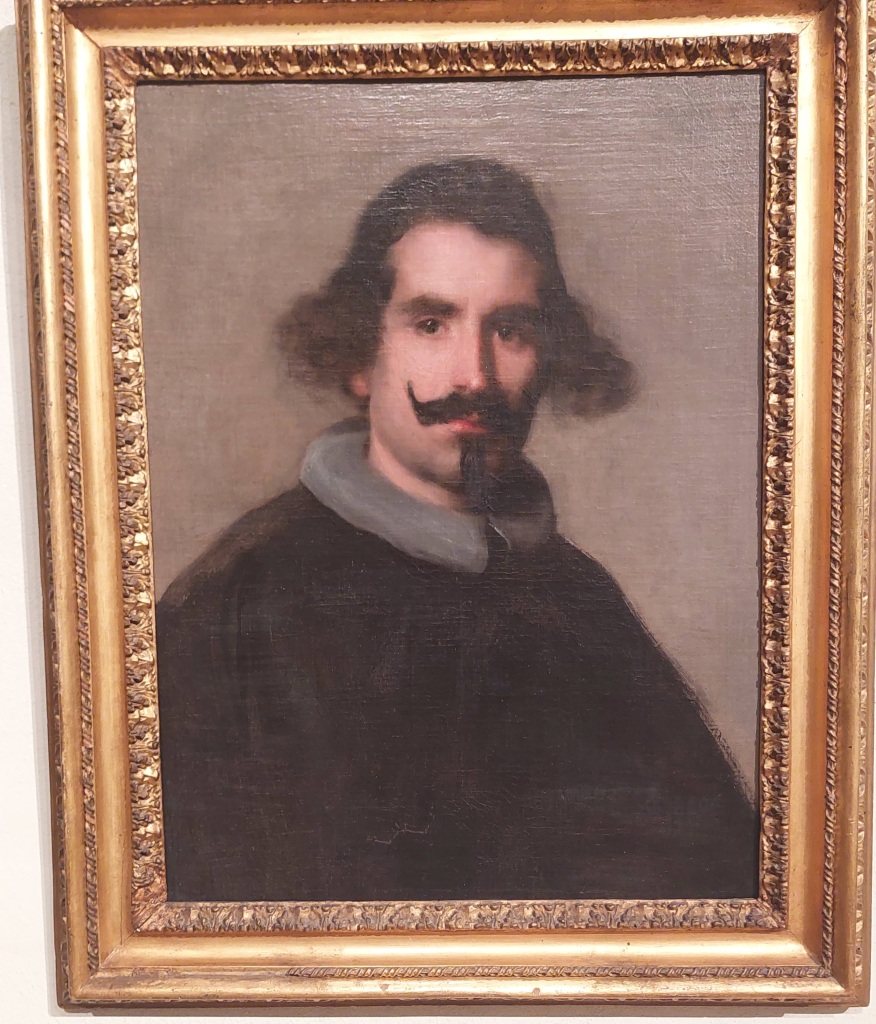

Another room is devoted to a portrait of Pope Innocent X, a member of the Pamphili family, by the Spanish painter Diego Velazquez. The painting was noted for its naturalness – unusual at the time for an official portrait of a powerful man.

I also liked this unusual double portrait by Raphael of the Venetian scholars Agostino Beazzano and Andrea Navagero – an affecting depiction of male friendship.

Art in Churches

You don’t have to go to museums to find great art in Rome. There’s a lot of it in churches. Entry to the churches is free, but you might need a few coins to illuminate the chapels.

The church of San Luigi dei Francesi, which has traditionally served the French community in Rome, has three paintings by Caravaggio, including the Calling of Saint Matthew. Matthew was, according to tradition, a tax collector – note the dubious reaction of the future Evangelist (the guy with the beard) when it appears Jesus is pointing to him.

The basilica of Sant’Agostino, which we have somehow missed on previous visits, has another Caravaggio, showing Mary holding a somewhat oversized Jesus and greeting several pilgrims. This church also has a wonderful painting of the Prophet Isaiah by Raphael, and a sculpture of Mary, her mother Saint Anne, and the infant Jesus, by Andrea Sansovino.

The sculpture of Saint Teresa in Ecstasy in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria , by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, is justly famous as one of the artist’s masterpieces.

More Raphael, in the church of Santa Maria della Pace.

Renovations of the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva are nearing completion, and you can see the wonderful frescoes by Filippino Lippi once more.

Saint Emidio, the patron saint of Ascoli Piceno, and protector against earthquakes, makes an appearance.

And of course, the churches themselves are pretty spectacular.

Castel Sant’Angelo

Somehow on our many visits to Rome, we had never visited this very famous site. To be honest, the interior wasn’t that interesting to us.

It did, however, offer some fantastic views of the nearby Vatican.

Some photos just walking around

Until next time!